A Time to be Silent, a Time to Shout

One of the great graces of being a Christian is to discover and cherish the Bible as a time-tested and trustworthy source of Divine wisdom. The Catholic Christian is called to benefit not only from these Sacred Scriptures (whose study often needs to be rekindled and deepened,) but also from two other sources of holy wisdom and unity whose origin is in Christ. These are the Church's Sacred Tradition [i], and its ongoing teaching authority (a.k.a. the Magisterium). The faithful Catholic has the duty and delight of humbly looking beyond the limited scope of his or her own experience and insights, to the inspired collective wisdom of the Church, as presented by the successors of St. Peter and the Apostles.

The diligent and prayerful study of these three sources – the Scriptures, Sacred Tradition, and the Church's Magisterium – provide the means for us to grow, over the course of our lives, to a certain maturity of insight and wisdom. But part of this maturity is in realizing that while the Pope and Bishops have been entrusted with teaching authority in the Church, not every word that they speak is thereby to be considered as divinely inspired. In fact, because of the human weakness and freedom of our Church leaders, they too are vulnerable to sin and error. And while we should always maintain proper filial respect for these successors of the Apostles, we also have the responsibility to be grounded in a wisdom that transcends their individual limitations, and is faithful to the perennial teaching of Christ and his Church.

This is all a lead-up to some important things I need to say about traditional and more recent understandings of the term sacred music, and the way in which these understandings have influenced the development of music in Roman Catholic liturgies throughout the world. We need to look closely and respectfully at the Church's official statements in this regard, in order to establish an appropriate definition for our own use in these blogs and podcasts. But before we do this, I'd like share a seemingly unrelated short story whose application to our present subject will become clear a little later on.

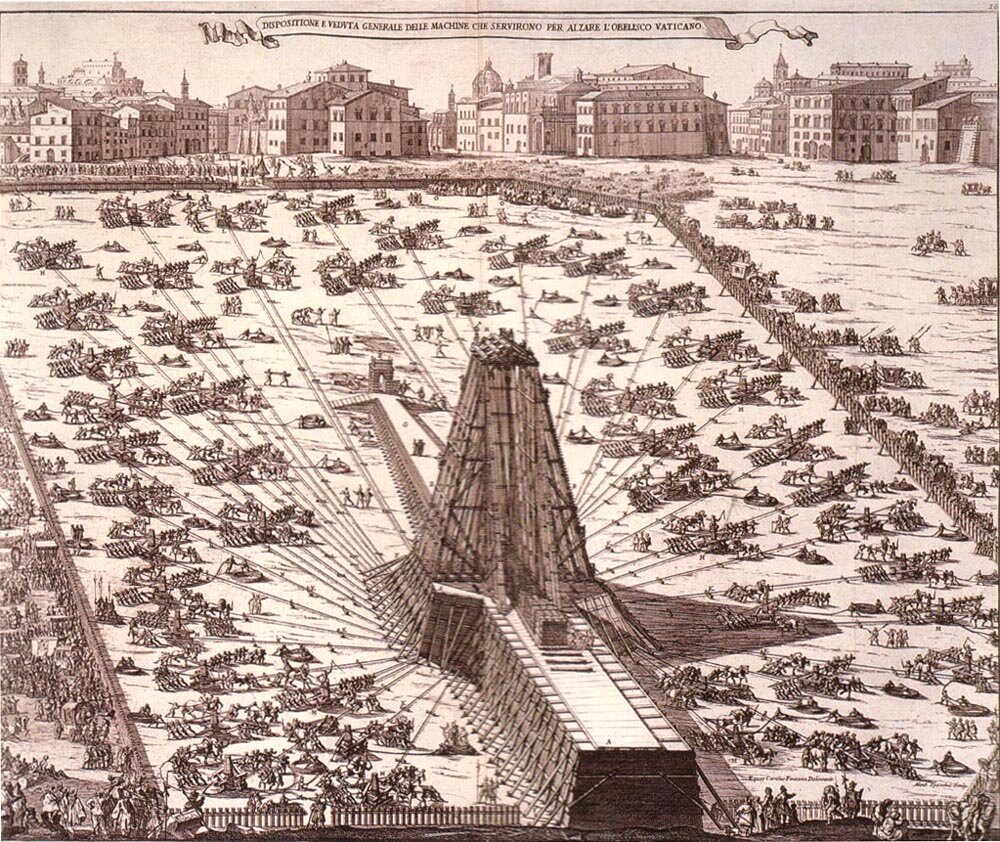

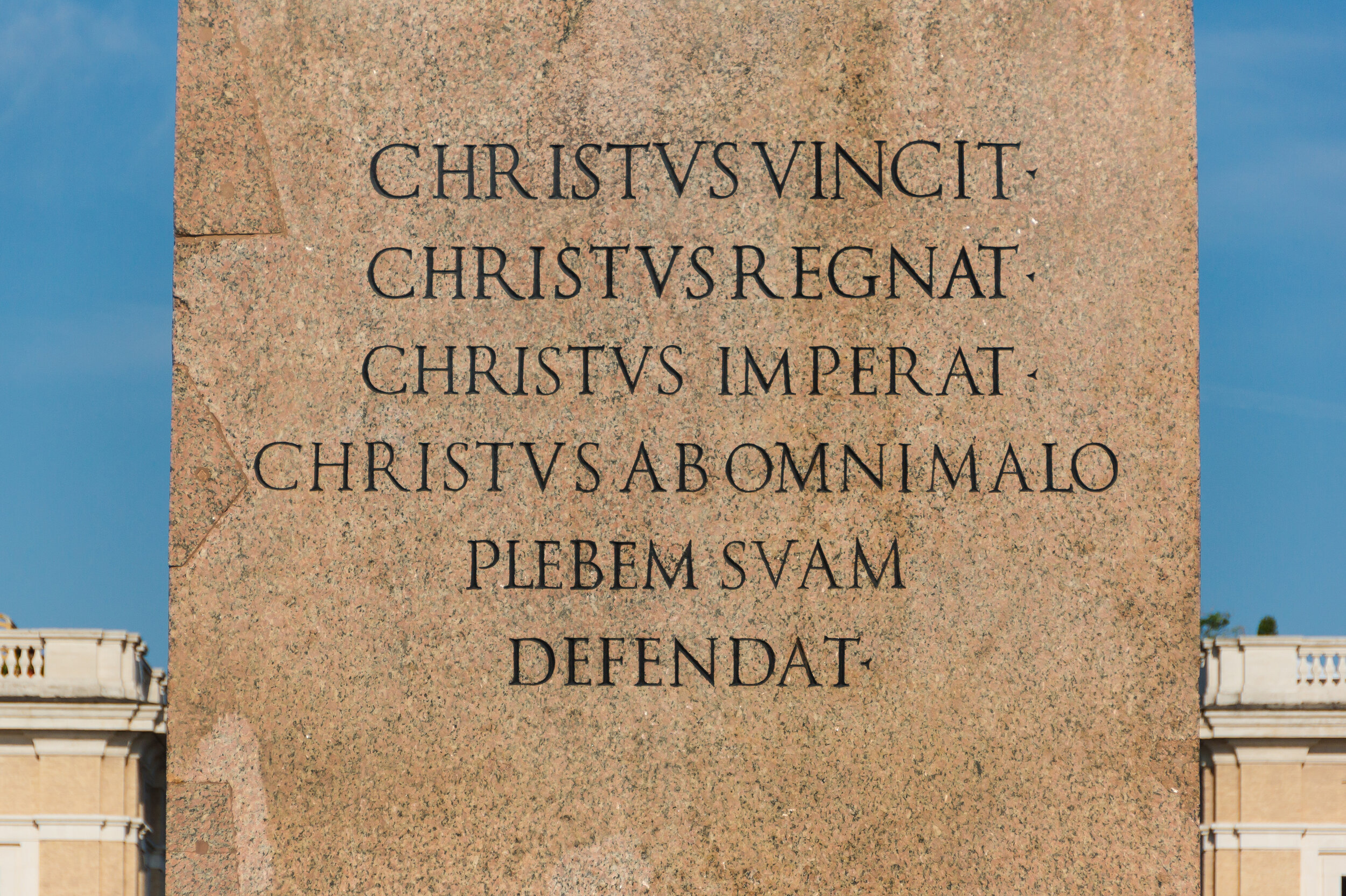

In the year 1586, Pope Sixtus V was having the construction completed of the new St. Peter's Square in Rome. As a finishing touch to this great endeavor, he ordered that the great ancient Egyptian Obelisk - which had been brought to Rome by the Emperor Caligula in 39 A.D. - be moved to the center of the Square. The obelisk was and is about 85 feet tall, weighing some 350 tons. To transport it, even the relatively short distance involved within the Vatican walls, was a task of colossal dimensions, involving some 900 workers, 140 horses and 44 winches. As it also demanded great concentration, orders were given by the Pope to the huge crowd in attendance that everyone must remain completely silent until the Obelisk had been placed firmly and safely in its new location. Anyone disobeying this strict injunction would be subject to the death penalty!

As the obelisk was being slowly moved through St. Peter's Square, the ropes began to show signs of fraying, and the immense object began to sway. It was at this moment that a seasoned sailor, Benedetto Bresca, shouted out from the crowd in his Ligurian dialect “Aiga ae corde!” which means “water on the ropes!” for the sake of making the ropes stronger and resistant to fraying and snapping. The workers followed his advice, and in so doing their task was saved from disaster. When Benedetto was brought before the Pope, whose explicit order he had defied, he was not only pardoned but also asked to name the reward he could be given for his heroic deed. According to legend, he requested that he and his descendants be allowed to be the Pope's perpetual supplier of palm fronds. And in fact the Popes have continued to receive their Palm Sunday palm leaves from Benedetto's home town of San Remo, up until the present day with just some brief interruptions.

Now what in the world does this have to do with sacred music? This story is an analogy of what has happened in much slower motion following the publication of two 20th century documents concerning sacred music, by church authorities in Rome. The first, written in 1958, is entitled De musica sacra et sacra liturgia – in English, “Instruction on Sacred Music and Sacred Liturgy” - and the second is the 1967 post-Vatican II document Musicam sacram, which in English is entitled the “Instruction on Music in the Liturgy.” Both of these documents contain inspiration and good instruction that is in harmony with the longstanding wisdom of church teaching. And where they have been embraced with piety and prudence, one can observe the good fruits of their implementation. But just as a few frayed ropes almost caused a disaster in transporting the obelisk, so also have a few problematic phrases in these documents – taken out of context – tended to undermine the great task of the renewal of sacred music that was envisioned by the Second Vatican Council.

And here we return to the definition of “sacred music”, for it is precisely in regard to this definition that we discover the frayed ropes. As mentioned in my last blog, the clear traditional meaning of this term has been “the music which has been uniquely created and consecrated for use in the Sacred Liturgy.” And as such, not only in the Roman Catholic Church, but also in all the Eastern Catholic Rites and in all the Eastern Orthodox Churches, it possesses by its nature:

the principal purpose of clothing the liturgical texts in suitable melodies which are able to draw the faithful into a deeper and more fruitful participation in the sacred mysteries. From this purpose it follows that it also must have

the attribute of being primarily vocal, even when the organ and other instruments are permitted and/or encouraged as a discreet accompaniment. Thirdly, it also has

a particular sacred character to its musical composition and performance which clearly distinguishes it from “profane” (not meaning “obscene”, but rather “outside the temple”) music. Pope Pius X identified this character by the three integral qualities of holiness, artistry, and universality, and by its harmonious compatibility with the Church's great tradition of sacred chant and polyphony.

All of the Church's 20th century documents on sacred music build upon this common understanding, as it had been clearly articulated by Pope Pius X in 1903. Vatican II's Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium (published in 1963) says for example:

The musical tradition of the universal Church is a treasure of inestimable value, greater even than that of any other art. The main reason for this pre-eminence is that, as sacred song united to the words, it forms a necessary or integral part of the solemn liturgy.

Holy Scripture, indeed, has bestowed praise upon sacred song, and the same may be said of the fathers of the Church and of the Roman pontiffs who in recent times, led by St. Pius X, have explained more precisely the ministerial function supplied by sacred music in the service of the Lord. [ii] [emphases mine]

However, this original definition of sacred music seems to have been almost imperceptibly modified in the 1958 document issued by the Sacred Congregation for Rites, in which it stated:

“Sacred music” includes the following: a) Gregorian chant; b) sacred polyphony; c) modern sacred music; d) sacred organ music; e) hymns; and f) religious music. [iii]

But it is assumed that not all of the above are necessarily appropriate for use in the Liturgy, as is stated later in the same document to describe the final category listed above:

Religious music is any music which, either by the intention of the composer or by the subject or purpose of the composition, serves to arouse devotion, and religious sentiments. Such music “is an effective aid to religion.” But since it was not intended for divine worship, and was composed in a free style, it is not to be used during liturgical ceremonies. [iv]

When Musicam sacram is promulgated in 1967, it quotes, makes reference to, and expands upon the above list from the 1958 document, but now seems to make very little distinction as to which of these forms are appropriate or inappropriate to the Liturgy. Here it is:

The following come under the title of sacred music here: Gregorian chant, sacred polyphony in its various forms both ancient and modern, sacred music for the organ and other approved instruments, and sacred popular music, be it liturgical or simply religious. [v]

While one might reasonably assume that this statement is sincerely trying to affirm the real potential for all the above categories to bring us closer to God, each in their own way, the problem seems to be this: that now, the essential distinction between the “sacred” and the “profane”, the liturgical and the non-liturgical, has been obscured.

But there is more to the definition of sacred music in Musicam sacram which might provide an important key to understanding the intention of this teaching. In the authorized English translation of this document, it also says that

By sacred music is understood that which, being created for the celebration of divine worship, is endowed with a certain holy sincerity of form. [vi]

What precisely is meant by the phrase “endowed with a certain holy sincerity of form”? While these might be thought-provoking words, they are in fact an incorrect English translation of the original Latin document, which says:

sanctitate et bonitate formarum praedita est.

This is a direct quote, with footnoted reference, from Pius X's motu proprio of 1903, and it unequivocally means “is endowed with holiness, and goodness of forms” [the latter is often translated simply as “beauty”.] Yes, in this original document the authors say nothing about “holy sincerity”, but they do affirm the first two essential qualities of sacred music articulated by Pope Pius; those attributes which he said would spontaneously produce the third essential quality of universality. And as we have seen before in previous posts, each of these three concepts provides a deep well of insight concerning sacred music, when considered in the light of our great traditions of chant and polyphony. But this vital connection seems to have remained hidden from the view of most English-speaking readers.

And indeed, the nearly universal interpretation of Musicam sacram was that the traditional distinctions between sacred and profane, beautiful and banal, universal and idiosyncratic, were to be rejected in favor of the “active participation of the faithful” (which properly understood would require such distinctions.) Apparently, sacred music no longer needed to be too concerned with the liturgical text, or communicate great reverence, or draw us into the transcendent Mystery of Christ's real presence. No longer did we need to honor our great sacred music traditions, or cultivate their virtues of sanctity, artistry, and universality in our new forms. Now there was “freedom” from the traditional parameters of wisdom and integrity to pursue whatever might seem to work best for you or me, or whatever might be most pleasing to most attendees of a given Mass in a given Parish. But when such so-called freedom is pursued to its logical conclusion, the result is invariably liturgical disintegration and polarization.

And so what must we shout out - figuratively speaking - in response to this confusion? Shall we plead that Musicam sacram be re-translated, and/or that the Church issue a new document that would lead us from confusion to clarity? While one might reasonably pray for such developments, we need to find a simpler script that is available to all of us in the meantime. And this message must be based on a principle found in all of the documents mentioned above, as each one of them begins by placing itself in the context of all preceding documents. Yes, just as C.S. Lewis eloquently insisted on the vital necessity of reading the “old” great books[vii] along with the new, so also must we study the “old” great teachings of our Catholic Faith, including those on sacred music! Only in this way will we be able to see the big picture, understand the whole story, gain mature wisdom, and immunize ourselves against the rampant cultural myopia in which we are currently immersed. For just as no book of the Bible can be fully understood in isolation from all the other books, so also can no document issued by the Church's Magisterium be fully understood apart from its other related teachings.[viii] And when we interpret Musicam sacram in this light, prayerfully studying it alongside the Church's other teaching documents on sacred music, confusion is dispelled and an inspired course of action becomes clear.

In this light, we are not obliged to throw out the traditional definition of sacred music; instead, we can embrace it while acknowledging that in certain circumstances it has been made more flexible so as to allow for holy adaptation and growth. We must never abandon the fundamental principles of sacred music, as articulated by Pope Pius X and others; instead, we must diligently apply them while also taking into account the important new factors which have been addressed in more recent documents. And “fully conscious and active participation” in the Liturgy must be understood in the way it has always been understood by the Church: as fully entering into the loving worship of God with all of our “heart, soul, mind, and strength.” That is to say, both internally and externally, with the former always having precedence over the latter. And so here is my working definition of Catholic sacred music, based on this integration of the new with the old:

Sacred music is music that has been created and consecrated for use in the Sacred Liturgy. As such it must share in the latter's essential qualities of holiness, beauty, and universality, in harmony with the Church's great traditions of sacred chant and polyphony. While its principle purpose is to clothe the liturgical texts with suitable melody, it can also be complemented by other worthy vocal and instrumental music, as charity, church law, and prudence might require.

So there it is, and I trust that this definition will serve our purposes well in the scope of these blogs and podcasts. However, it is doubtful that it would have the efficacy of “aiga ae corde” or “water on the ropes” as we bring it to the throng of clergy, church musicians, and laity with whom we work. And so, what should we proclaim? Is there a succinct phrase we can use, with charity, audacity, prudence, and perseverance, that can engage people's attention and inspire them to diligent action? Here is my suggestion, which is remarkably unoriginal, being just about as time-worn as a captain's orders to pour water on the ropes. But it is still filled with the same power as when it was first formulated over a hundred years ago. From our own sure footing in the wisdom that transcends current trends, let's shout out, not only in Rome but also throughout the entire Church, that

“Sacred music must be HOLY, BEAUTIFUL, and UNIVERSAL!!!”

And then when asked what this means, we will be able to graciously explain that:

To be holy means that it must serve its primary purpose of clothing the sacred text of the Liturgy, it must be in organic continuity with our great traditions of sacred chant and polyphony, it must be clearly distinguishable from non-liturgical (“profane”) music, and it must have the capacity to draw people into the transcendent Mystery of the Liturgy.

To be beautiful means that in both composition and performance, it is done with skill so as to bring holy delight to those who hear; this does not necessarily require sophisticated or professional singing skills, but does require diligent attention and preparation. And just as with the sacred beauty appropriate to an icon, it must always modestly point away from itself to the transcendent reality which it serves.

To be universal means that it does not serve only one group of people, but rather has the capacity to resonate deeply across the broad spectrum of personality types, ethnicities, cultural levels, age groups, etc. of which our Church is comprised.

Whatever might be the apparent success or failure of this message, let's continue to strive for the maturity of wisdom that integrates the new with the old. And let's diligently apply the fruits of this wisdom in our silences, in our words, and in our actions. Thus shall we move forward confidently towards the renewal of sacred music in our parishes and communities – a mission that is immeasurably more important than the moving of the great obelisk to the center of St. Peter's Square.

[i] To be precise, the Bible belongs to the Sacred Tradition, being authoritatively compiled and handed down through the authority which Christ vested in his Church. But because of its preeminent and unique role in this Tradition, it is listed separately here.

[ii] Sacrosanctum Concilium, no. 112

[iii] De musica sacra et sacra liturgia, no. 4

[iv] Ibid., no. 10

[v] Musicam sacram, no. 4b

[vi] Ibid., no. 4a

[vii] C.S. Lewis, Introduction to On the Incarnation, St. Athanasius; see here

[viii] For a listing of some of these documents, see my post from Dec. 13, 2019: “The Art of Renewal – Part II”. As mentioned there, one of the most invaluable references in this regard is: Papal Legislation on Sacred Music, 95 A.D to 1977 A.D., compiled by Msgr. Robert Hayburn (Published by Liturgical Press, 1979 and